|

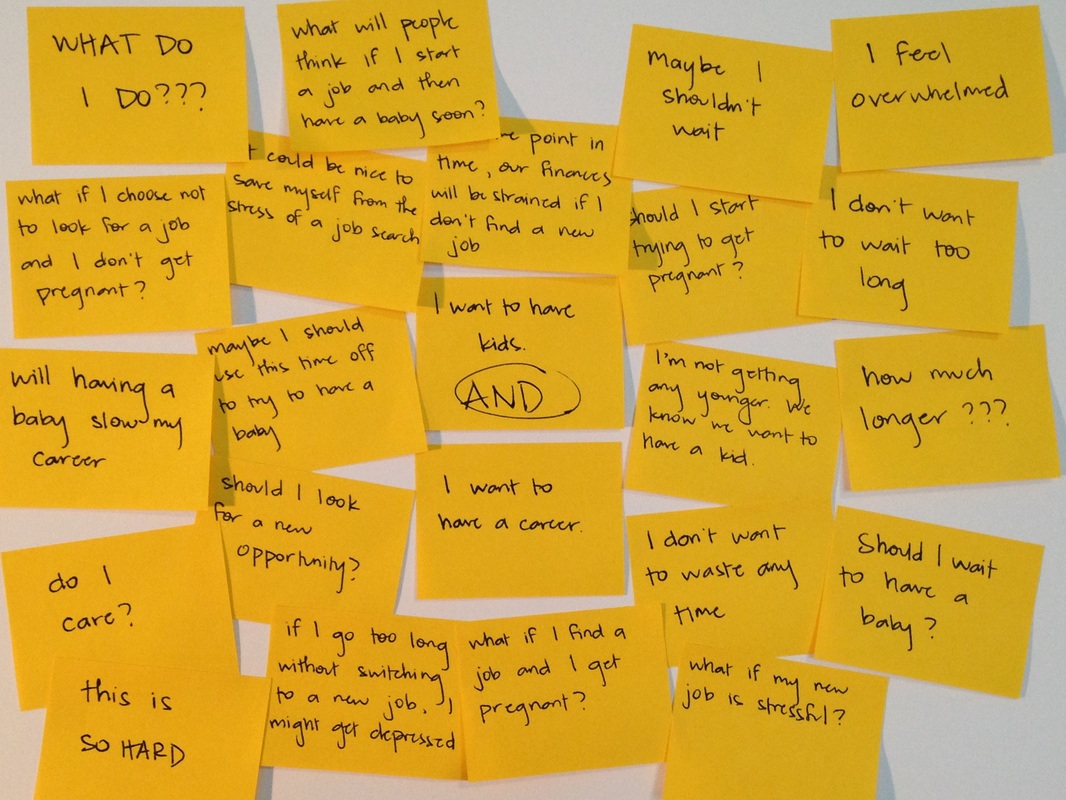

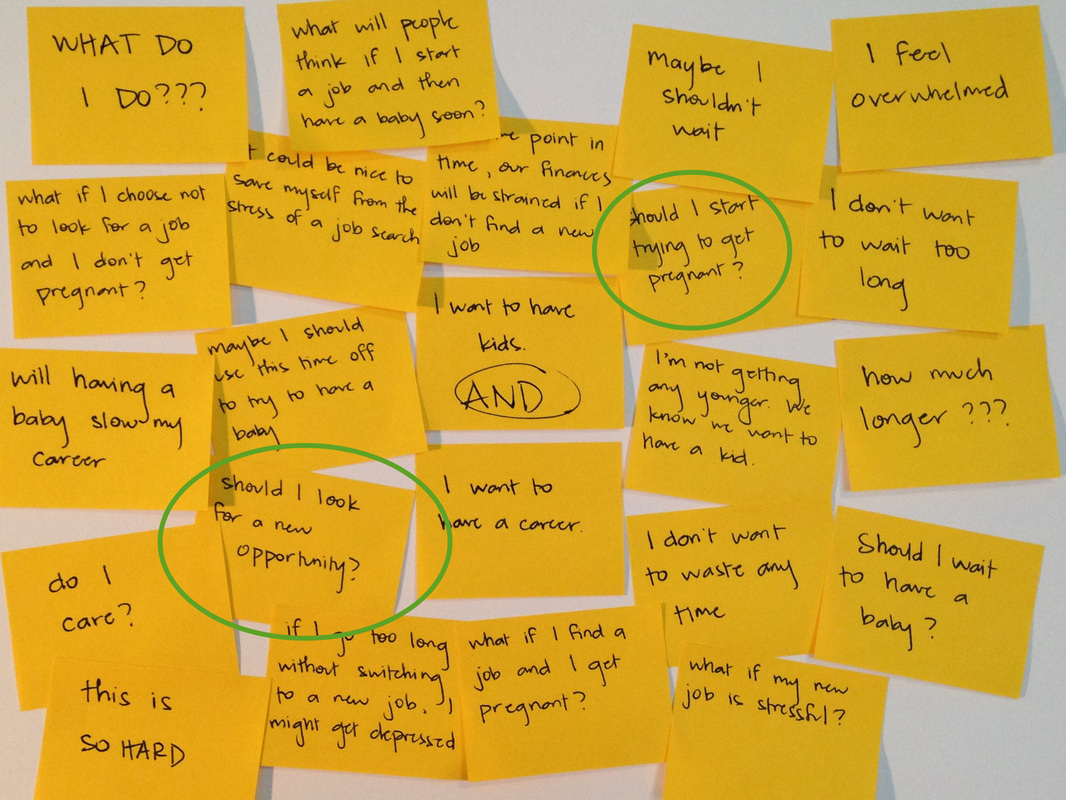

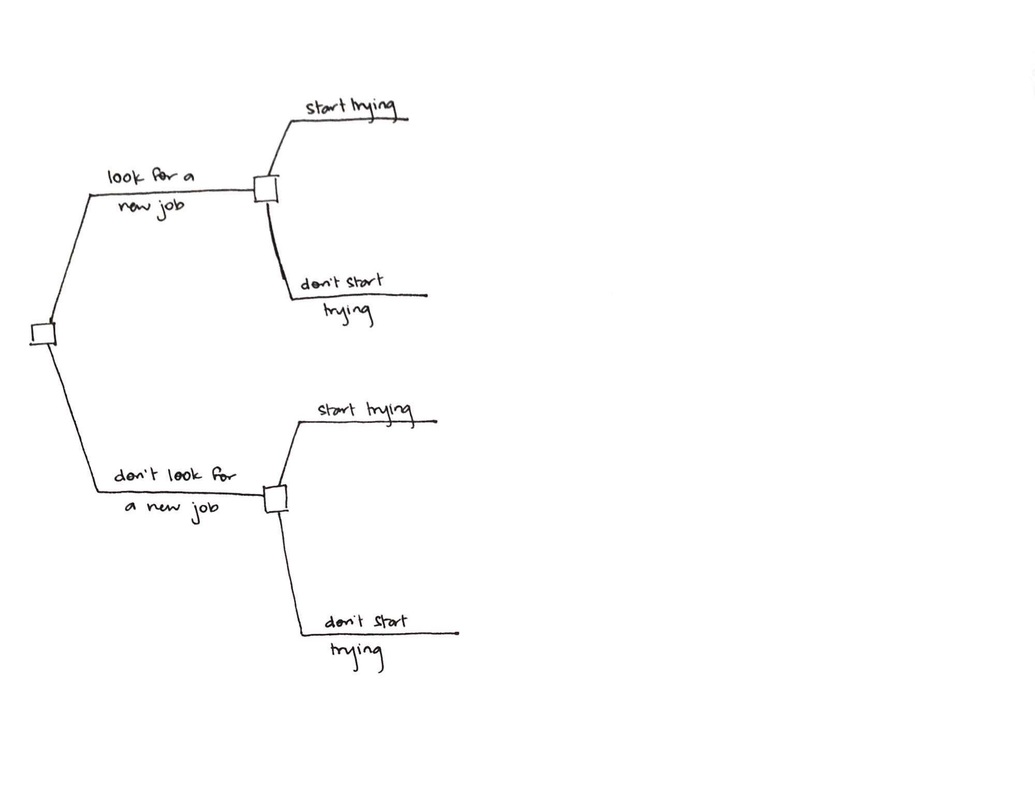

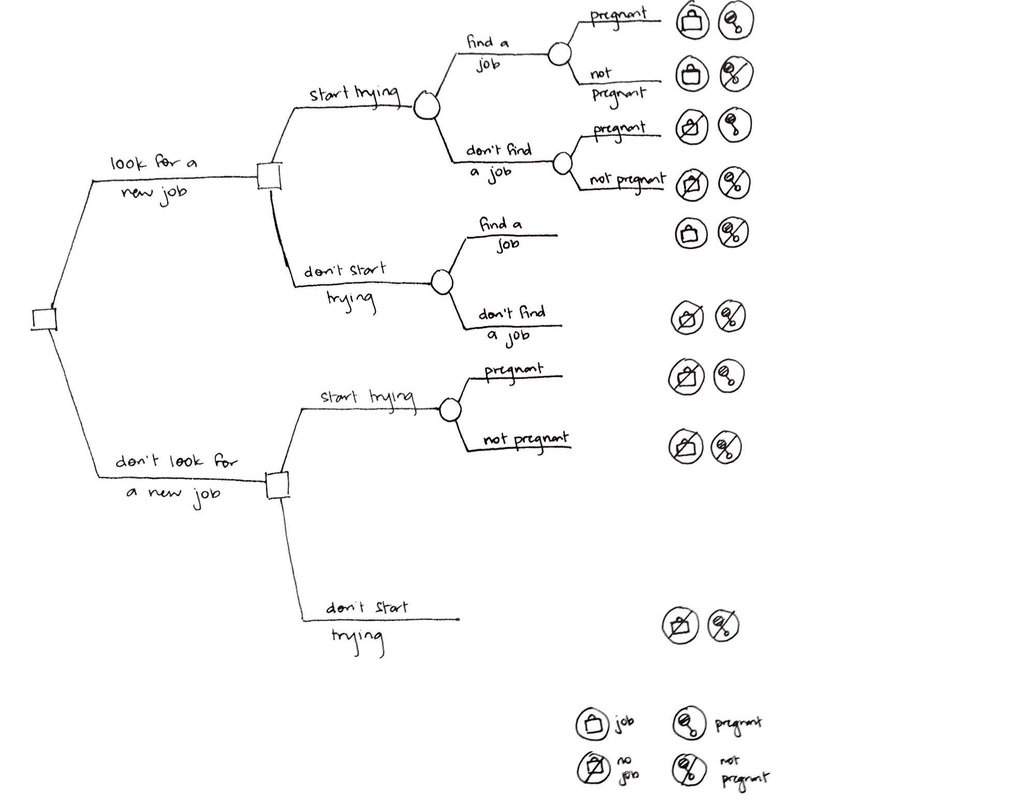

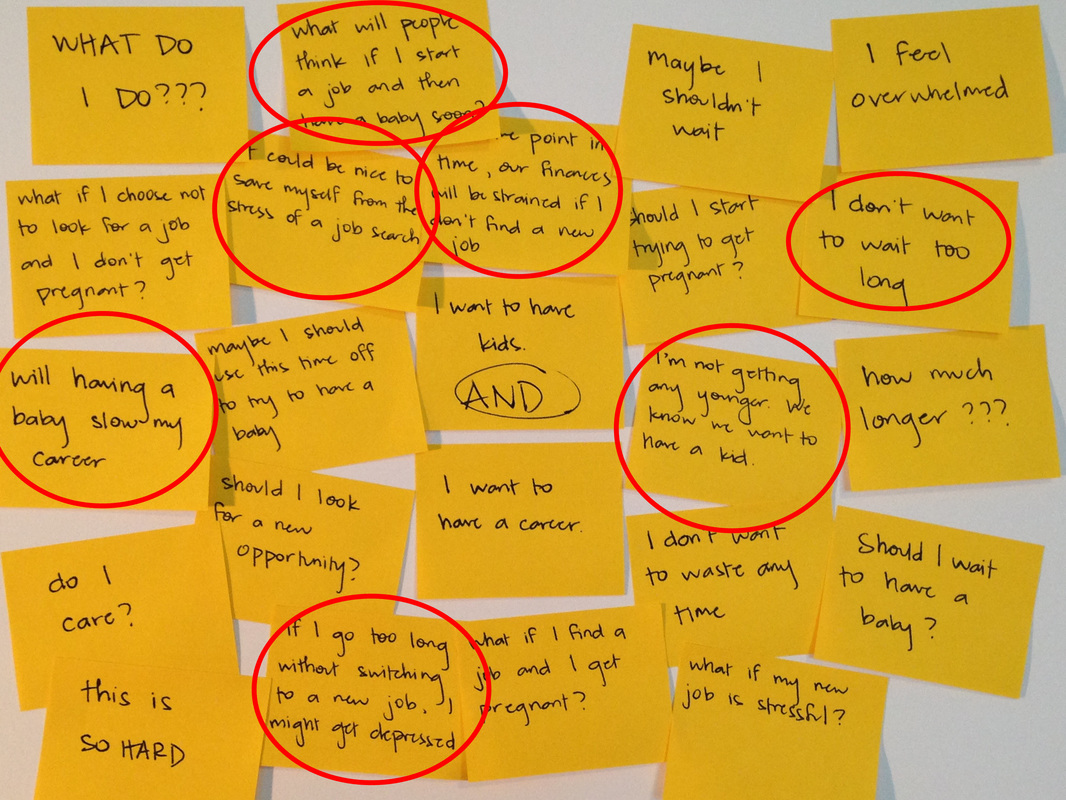

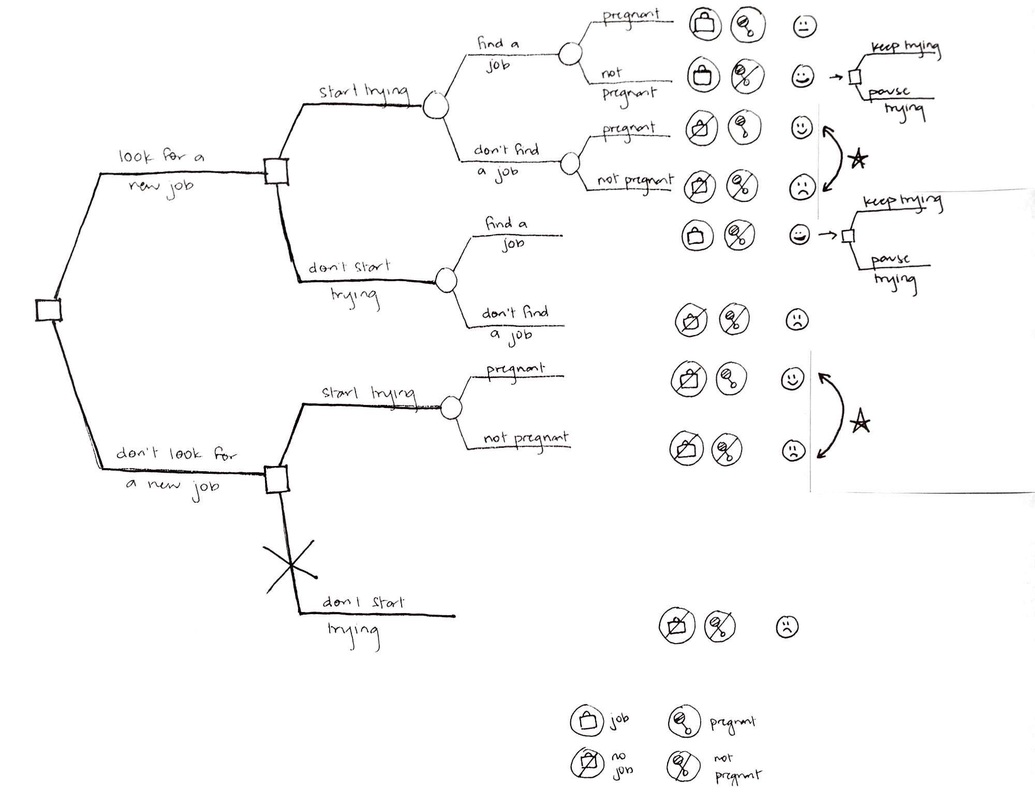

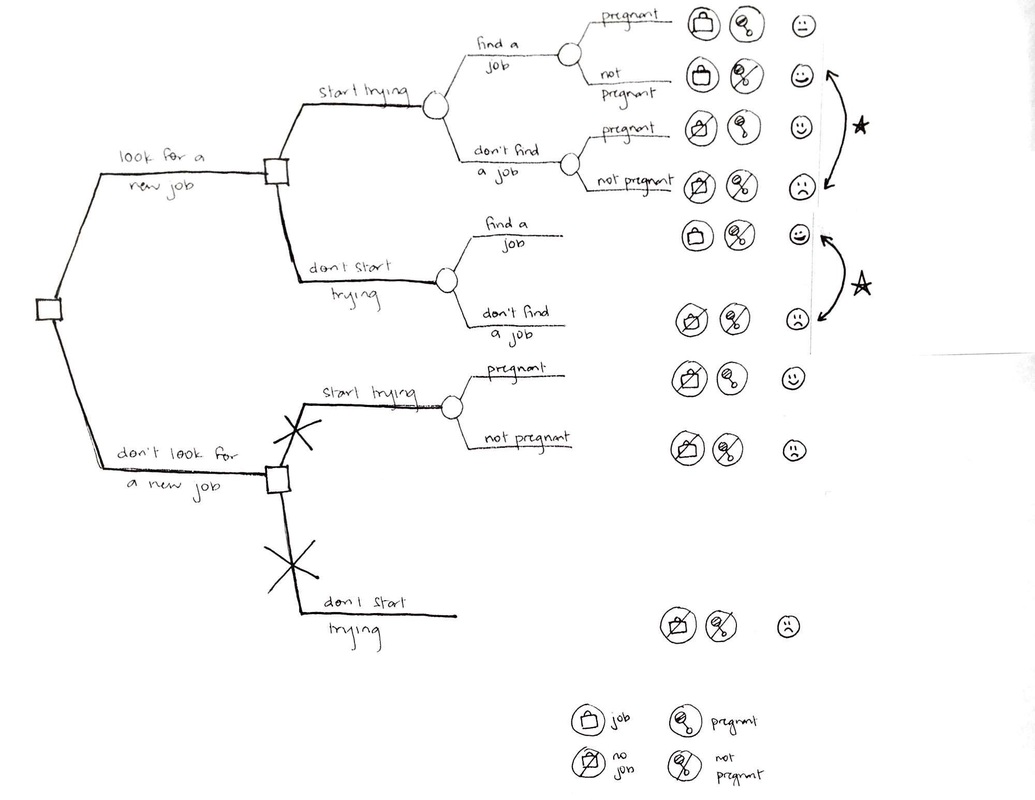

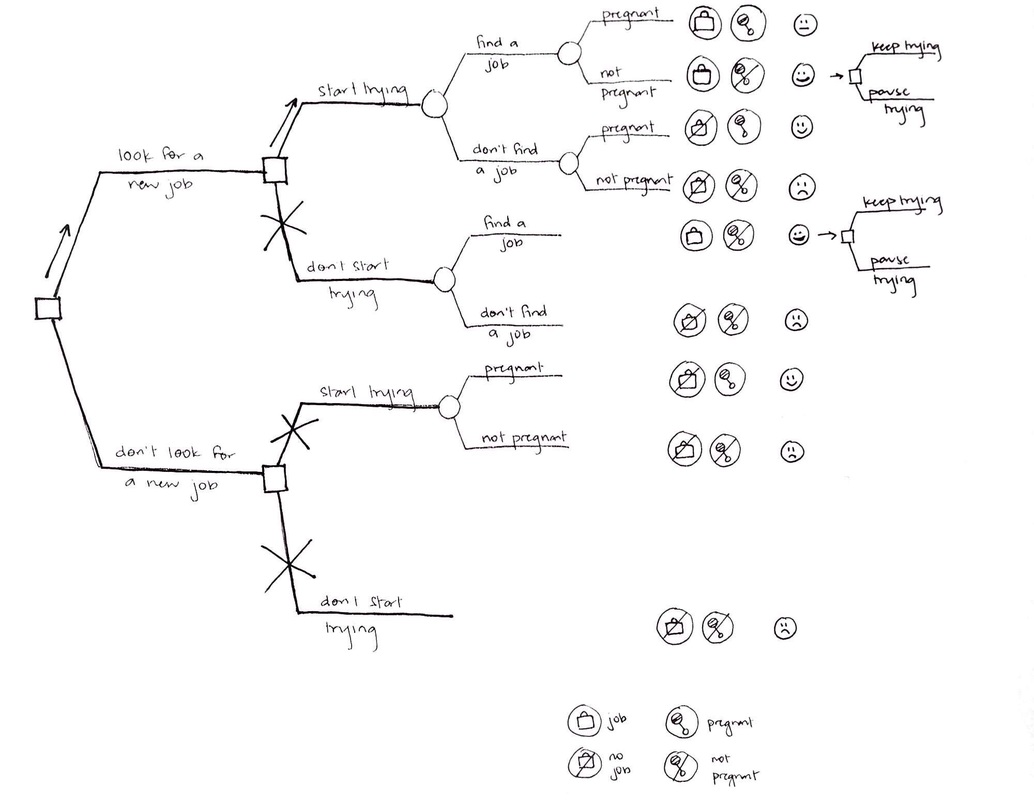

I never realized just how much anxiety was triggered by decision making until I began sharing with people that I studied decision engineering at Stanford. “That’s neat! I hate decisions. Can you help me?” “That’s a thing? Why don’t they teach that to everyone? I could totally use that.” “Wow. Can I just outsource all my decision making to you?” I absolutely love the process of untangling decisions. Most people don’t. They run the other way. And when they do face one, it can feel confusing, emotional, stressful, and overwhelming. But it doesn’t have to be that way. One of the best things you can do to avoid thinking in circles is to get all of those thoughts about the decision out of your head and onto paper, into a decision tree. A decision tree is a visual representation of the decision(s) you have to make, the uncertainties in play, and the possible outcomes you may face. Once your thoughts are mapped out outside of your head, it becomes easier to evaluate what course of action makes sense. Let’s take, for example a common dilemma faced by a number of professional women. Recently someone hired me because she was stressed out about decisions regarding her career and starting a family. I asked her to spend a few minutes sharing the thoughts that ran through her mind when she began to feel stressed about this area of her life. Here’s a picture of what I captured from her brain dump. The first step in mapping out a decision tree is to identify what is/are the decision(s) you have to make. Because decision trees work best when you’re dealing with decisions that have 2-3 options, look for the decisions that are concrete enough to tackle. For example, “What do I do?” is too broad and can go in too many different directions. Also, if you have smaller decisions that relate back to a bigger decision (e.g. “How much longer?” is a decision preceded by “Should I wait to have a baby?”), focus on the bigger decision first. There were two main decisions that came up in what my client shared: “Should I look for a new opportunity?” “Should I start trying to get pregnant?/Should I wait to have a baby?” The two decisions are independent of one another, and neither is contingent on additional information, so we can use both to anchor the beginning of our decision tree. Decision nodes are commonly represented by squares. If you’re not sure whether you’re anchoring your tree in the right decisions, don’t worry. Just start somewhere. Later on, if you find that another decision pops up no matter where you go in the decision tree, you can redraw your tree. What’s important is that you start somewhere, because the simple act of getting your thoughts down on paper leads to more insight and clarity. Next, identify the uncertainties in play. Decisions are things that you can control. Uncertainties are things that you can’t control. My client can decide whether to begin trying to get pregnant. She can’t control whether she actually becomes pregnant. My client can decide whether to look for a new opportunity. She doesn’t control whether she will actually find one. Map out the uncertainties, represented by circular nodes. Now that you’ve mapped out the various possibilities that may play out as a results of your decisions and the uncertainties, note the outcomes of each branch. Now, go one step further and evaluate each resulting state. To what degree does each outcome help you achieve what you ultimately want, i.e. to what degree does each outcome fulfill your objectives? If you’re not clear on what your possible objectives were, go back and examine the other thoughts that may have made the decision difficult. My client wanted to have a child. And she wanted to have a career. She also worried about things like “not getting any younger”, how “finances will be strained” if she doesn’t find a new job, “what will people think” if she starts a job and then has a baby soon, and the impact of stress on having a child. Translated, the objectives floating around in her head included:

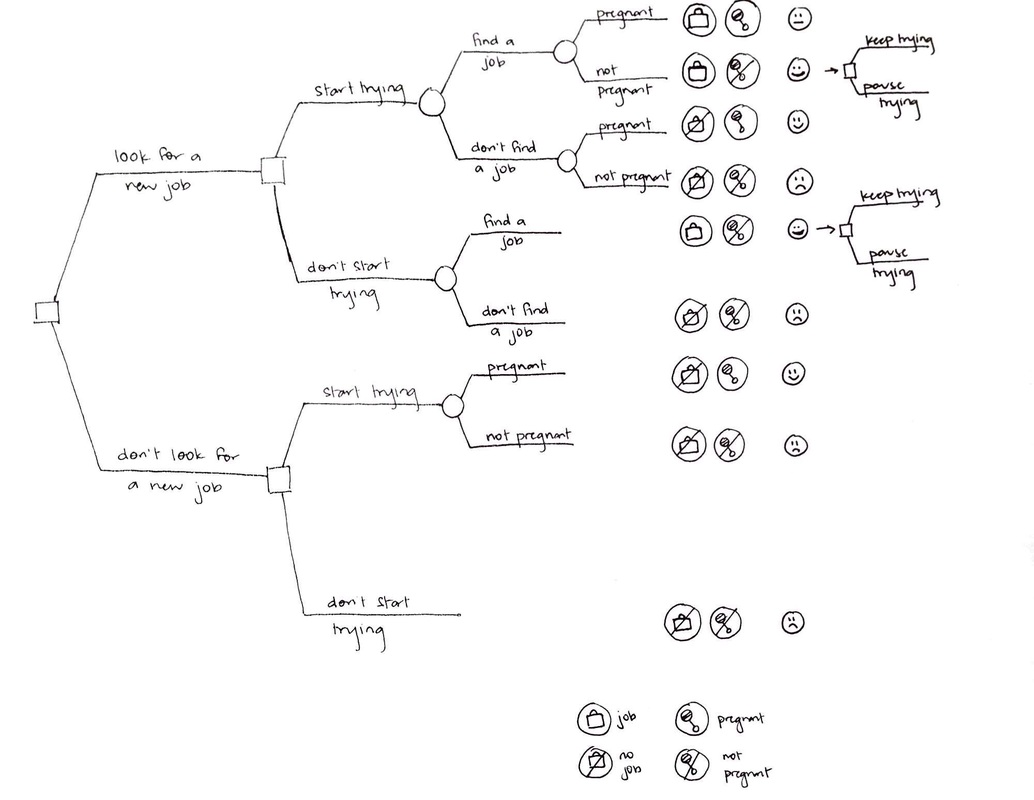

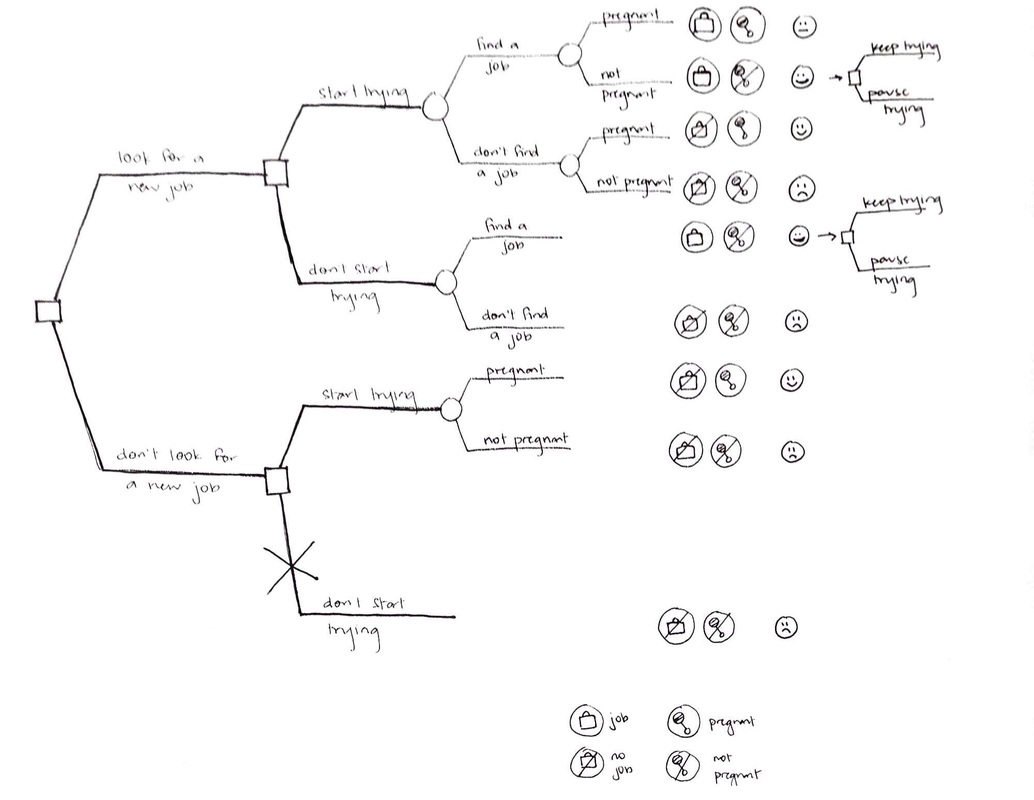

My client’s highest priority objectives were to have a child, to have a career, and to minimize stress. Based on those priorities, she rated each outcome according to how well each one met her objectives. For my client, the worst possible outcome was not being pregnant and not having a job. A good outcome was being pregnant and not having a job. (She would pick up her search after having a baby, and it gave her a good explanation for the gap in work on her resume). A mediocre outcome was getting pregnant and finding a job, because of the stress that would come from being pregnant and having to prove herself in a new job. The interesting thing about finding a job and not getting pregnant was that she could make a new decision at that point: pause trying to get pregnant while she ramped up at her job. As a result, she rated that outcome as positive. After evaluating the outcomes, it came time to see if the tree could be pruned. Choosing not to look for a job in conjunction with choosing not to try to get pregnant resulted in a negative outcome, so we eliminated that branch. Now, let’s compare the branches that involve choosing to start trying. If combined with the choice not to look for a job, the outcomes are positive or negative. When combined with the choice to look for a job, you may get the positive or negative outcomes, but you also the the possibility of a positive or mediocre outcome as well. If my client chooses to start trying, she is better off looking for a new job than not looking for one. Since we’ve eliminated both of the lower branches, it’s time to compare the choices stemming from the choice to look for a job. The outcomes of choosing not to start trying can also be achieved when you choose to begin trying, but the choice to begin trying has the added possibilities of a positive and mediocre outcome, which is a net improvement over choosing not to start trying. So, based on this analysis, looking for a job and beginning to try to get pregnant are the choices that will maximize my client’s ability to meet her objectives. Of course, even after this analysis you may still feel uneasy. That’s ok. That’s the fear. If you have any uncertainties in your tree, there will still be fear. If you have any possibility of any outcome that is even slightly negative, there will be fear. Making good decisions is not about eliminating the fear. Making good decisions is about acknowledging where the fear is coming from, and choosing to act anyway.

Mapping your thoughts out on paper will put you in a better position to rationally process what is making your decision difficult. If your tree has too many branches, you may need to do a deeper dive into evaluating and pruning your options before you take uncertainties into account. An inability to evaluate the outcome of each branch indicates where you may need to gather more data. If you are able to draw out a simple tree, it may also shine a light on paths that are easy to eliminate or outcomes that are equivalent regardless of the choices you make. Ultimately, decision trees can help you focus on what truly makes a difference, and move forward from there.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed